Depending on how old you are, I am willing to bet you have a memory of tomato juice connected to someone you love. For many of my millennial peers, this memory is about grandparents and parents who always had the thick, red juice on hand.

I grew up in Ontario in the 1990s and early 2000s, and my family was always a tomato juice family. At family gatherings, there were two options for [non-alocholic] drinks: milk or tomato juice.

Then, flipping through my embarrassingly extensive collection of old cookbooks, I began thinking about tomato juice a little bit more. What happened to it? Why do I only drink it in cocktail form? Is this a personal problem? No, it’s probably society at large. Then when did it go out of style and why?

I have ventured to answer this question by looking through my cookbooks (not hard), thinking about history (challenging in a fun way), and writing after the kids go to sleep (nearly impossible).

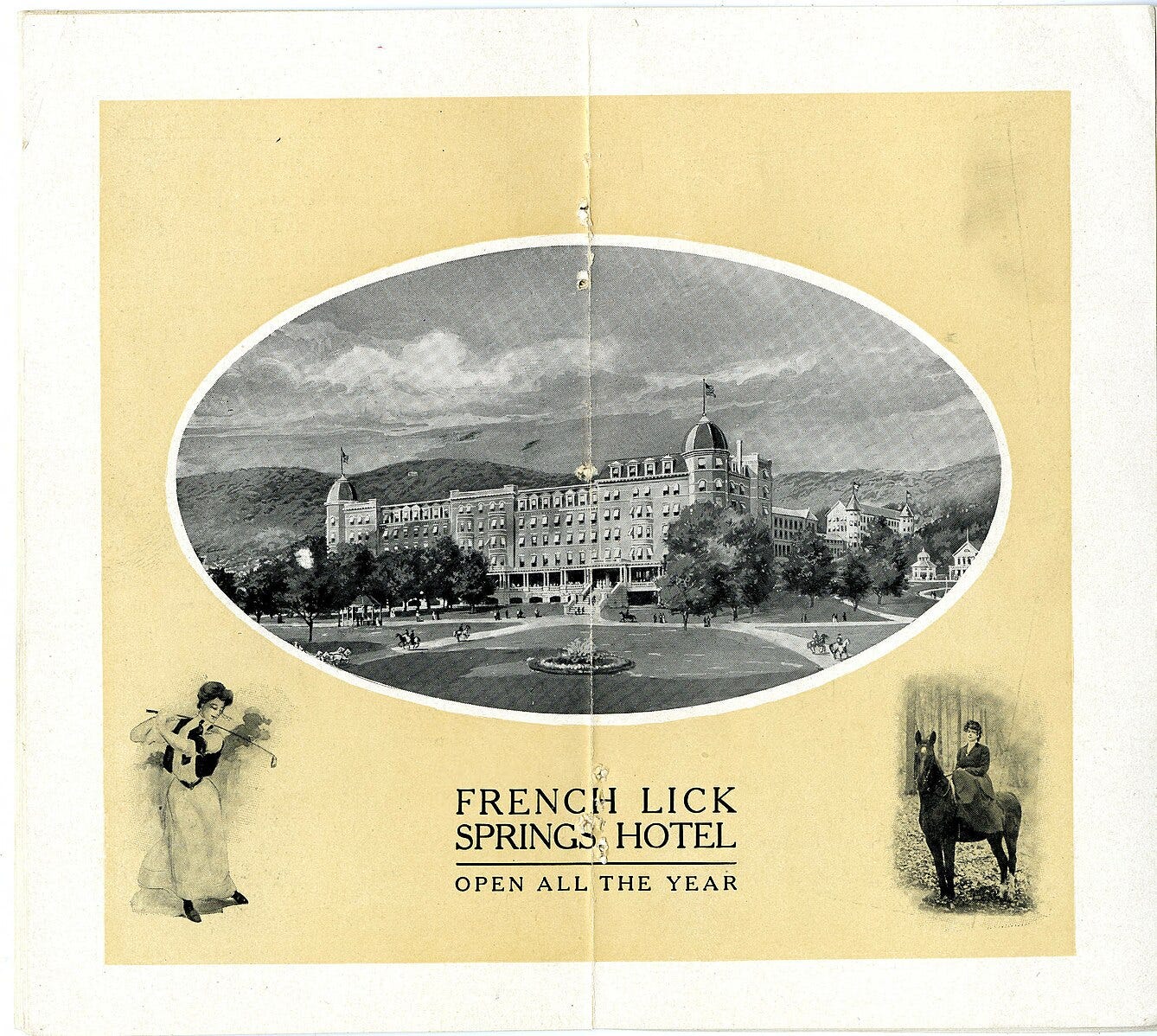

The Man, the Myth, the Resort Drink

Tomato juice, so the story goes, was invented in 1917 when Chef Louis Perrin, who worked at a resort hotel in French Lick, Indiana, ran out of oranges and juiced tomatoes instead.

The drink proved so popular that French Lick began producing it at scale. Every retelling of the story glosses over the production and distribution of the product in French Lick, mind you, but finishes with the kicker that by 1928, tomato juice was being canned and produced industrially, putting French Lick out of business.

Following the mechanization of its production, tomato juice became ubiquitous on restaurant menus, in recipes, and at American breakfast tables.1 (And maybe at your grandpa and grandma’s house.)

This story raises so many questions that I have my suspicions on its accuracy.

Maybe I’m a cynic, but I’m going to guess Chef Louis Perrin could have squeezed a number of other fruits that were not a tomato, and in doing so, avoided the hassle of skinning, straining, sugaring, and spicing the finicky little things.

On the other hand, if he did have a “secret sauce,” that he added to his concoction, as so many retellings state, I’m dubious he pulled it out of nowhere on the first try. What I mean is, Chef Perrin was just as likely as not planning and tinkering with that recipe for a while.

Chef Perrin, of course, was not the first human to juice a tomato. He probably wasn’t even the first person to juice a tomato in Indiana. (Jury is out on being the first in French Lick—it looks small.) Indeed, people across America had been juicing tomatoes for a while and waxing poetic about their health properties.

Once in a while, you’ll find it cropping up that Americans were terrified of the tomato through the nineteenth century. Andrew F. Smith, in The Tomato in America, has argued quite convincingly that this was not the case. In fact, if you want to read something where you can almost hear the author sighing in frustration, read the introduction to that book where Smith pushes back against all kinds of tomato tomfoolery.

Smith’s book covers pre-Civil War American tomato culture, and in it, he shows that there were many recipes for tomato drinks, sauces, and condiments. During his period of study, people (mostly women) were using sugar as an additive as a way to preserve the tomato, because that is the method they had at their ready disposal at the time. So, his research reveals, tomato wine and syrup recipes cropped up in nineteenth century cookbooks.

Not only that, Smith elucidates the vigorous campaign to promote tomatoes as medical cure-alls in the early-to-mid 1800s.

Essentially, there was a large tradition upon which Perrin (born in the 1860s) was likely drawing when he juiced his hotel tomatoes.

But let’s just say, for argument’s sake, that Chef Perrin did just decide to strain a tomato one day out of desperation. A question about why it took off in such an extraordinary way remains. Were people across the United States and Canada so impressed with French Lick, Indiana that they simply had to have the drink served once at breakfast to a handful of people who liked it? Were they all closely following the Indiana hotel haute cuisine scene? All of this seems extremely doubtful.

The Bigger Picture

So what did happen with the tomato juice? I’ll speculate by thinking a bit big.

If we focus out from French Lick, there was a lot going in 1917 when Chef Perrin purportedly invented the drink. First, we can’t forget that World War I was three years into its run in Europe. During this time in Britain, pre-enlistment medical examinations gave a fuller picture of the nourishment of society at large than ever before, and the results were not great. Nourishment, then, was on the minds of US leaders when the country entered the war—coincidentally around the same time tomato juice burst onto the scene.

Not only that, but the government was thinking about nourishment in a new way due to some recent major scientific advancements. Both the vitamin and the calorie were discovered in the early decades of the twentieth century. So, by the time US troops joined the meleé, Woodrow Wilson, then the US President, had created a national food authority that was stressing the importance of food in a quantifiable, mathematical way, both at home and abroad.2

On top of all of this, the technology of canning was coming into its own. Production of canned goods had increased substantially over the course of the nineteenth century. By the early twentieth century, canned food was more accepted, more ubiquitous, and more affordable than ever before.3 Now, instead of using sugar to preserve tomatoes at home, the ephemeral freshness of the tomato could be preserved in a can.

With all this in mind, tomato juice began being touted as a health drink, likely with the power and support of the government behind it, and definitely with more scientific and academic study. These changes dovetailed nicely with Chef Perrin’s discovery.

Prohibition likely assisted tomato juice’s rise, as did freezing technology. Tomato juice survived the freezing and shipping process much better than its would-be competitor, orange juice, which didn’t become popular until after World War II.4

But what happened to tomato juice? If you flip through many post-WWII cookbook, you’ll probably see tomato juice on the menu, generally as an aperitif or a brunch drink.

The Joy of Cooking notes in its juice section—which includes tomato juice—that juices are for “those who cannot take cocktails because of their alcohol content and those who like to appear convivial but who are convinced that a stiff alcoholic drink before dinner blunts the flavor of food.”5

With the discovery of the calorie, there also came calorie counting. Tomato juice became a darling of those watching their waistlines during the postwar period, too.

But the ubiquity of tomato juice falls off around the 1980s. While some may contend it was a popularity issue, I have another theory: the great sodium scare.

While we pay a lot of attention to the low-fat health trend that surfaced in the 80s, we tend to forget that a similar low-salt trend accompanied it. Several high-profile studies in the 70s and 80s discouraged heavy salt intake, and I assume that tomato juice took a hit. After all, its salty quality is one of its best qualities.

Today, the vestiges of tomato juice live on in our lives, hinting at its former glory. You probably have some recipe with old roots that you like that uses tomato juice. (It’s in my favorite beef stew recipe.) And let’s not forget that we still drink Caesars, Bloody Marys, and Micheladas in great numbers (though ideally not at one sitting).

Or, maybe you still have a can of tomato juice as a drink once in a while. I definitely did through some particularly punishing bouts of morning sickness. Over ice, the stuff still hits the spot.

Google French Lick tomato juice and you will find several renditions of this tale. Here’s one: https://www.historichotels.org/us/hotels-resorts/french-lick-springs-hotel/restaurants/the-original-tomato-juice.php.

There is an exceptional book that goes into the discovery of the calorie in detail at the beginning and the Green Revolution more broadly called The Hungry World by Nick Cullather.

For all things canning in the US, see Anna Zeide, Canned : The Rise and Fall of Consumer Confidence in the American Food Industry.

“The Surprising Link Between World War II and Frozen Orange Juice” by Emelyn Rude.

Joy of Cooking has been published many times since its original run in 1931. My copy is from 1975. I’m not sure when this text is from.

Tomato juice is a staple in our house. My kids eat it as soup, and we put it over pasta all the time! Pasta with tomato juice was my grandmothers favorite breakfast—and we have continued that tradition!

Holy moly! I did not know the long and complicated history of tomato juice. I still make tomato juice from our home grown tomatoes and use a hand crank juicer like the one my parents had. We rarely drink the juice but use it to make tomato soup, spaghetti sauce and of course stuffed cabbage. Thanks for all the history and the memories stirred up!